Can the Chemical Industry Move Beyond Portland Cement?

The options available for raw material suppliers hoping to make headway for sustainable construction feedstocks.

For an industry built on scale, cement has an uncomfortable problem: it is both indispensable and deeply carbon-intensive. Traditional Portland cement still dominates global construction, but rising energy prices, carbon costs, and pressure from regulators are forcing manufacturers to look hard at alternative raw materials.

The big question for raw material traders and the wider construction industry is not whether alternatives exist — they do — but whether they can compete on price, availability, and performance at an industrial scale.

Why Portland Cement Is So Hard to Replace

Portland cement’s strength lies in its brutal simplicity. Limestone is abundant, the chemistry is well understood, and the supply chain is mature. But the process comes with two structural disadvantages that are becoming harder to ignore.

First, limestone calcination releases CO₂ by definition — even before energy use is counted. Second, clinker production requires temperatures of around 1,450 °C, causing producers to consume large amounts of fuel even though energy markets have become so volatile.

From a trading perspective, this means exposure to fuel costs, carbon pricing, and increasingly unpredictable regulatory intervention.

Alternative Raw Materials: What’s Actually on the Table?

Several competing material routes are now being tested or commercialised, but each brings its own opportunities — and headaches — for industrial supply chains.

Geopolymers

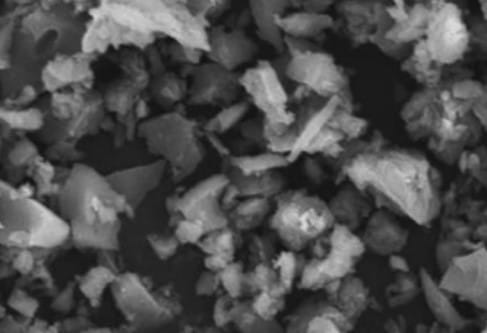

Geopolymers are often presented as the most credible long-term alternative. Instead of limestone, they rely on aluminosilicate sources such as fly ash, blast furnace slag, calcined clays, or metakaolin, activated using alkaline chemicals. The attraction is obvious: no clinker, lower kiln temperatures, and significantly lower direct emissions.

However, sourcing regular supplies of fly ash and slag is becoming harder, as coal and steel production is available in some regions and in others not at all. At the same time, alkali activators, like sodium hydroxide and sodium silicate, are energy-intensive chemicals in their own right, which means that the carbon burden is merely shifted upstream rather than being eliminated.

Supplementary Cementitious Materials

Supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) are often seen as a middle-road towards sustainability. By partially replacing clinker with slag, fly ash, or calcined clays, producers can reduce emissions while keeping existing plants and standards largely intact. This more conservative approach is already commercially viable, but it is still limited by the availability of suitable SCMs. It also fails to completely remove the use of clinker as a raw material.

Bio-additives

Bio-additives and lightweight fillers, including cork waste, natural fibres (such as wheat stalks, hemp, or Kenaf stems), and recycled organics, are gaining attention as performance enhancers rather than full binders. Cork, for example, can improve thermal properties and reduce density in geopolymer mixes while still using a recycled waste product.

However, raw material traders need to be cautious in supplying these feedstocks, as they exist only in niche secondary markets with irregular or seasonal sourcing. Consistency, geography, moisture sensitivity, and logistics costs can also restrict their availability.

Magnesium-based and Alternative Eco-cements

Modern developments in construction feedstocks have offered magnesium-based products as alternative cement feedstocks. While these do show the promise of lower firing temperatures and, in some cases, CO₂ absorption during curing, the supply chains are far from mature. This means that while the chemistry is attractive, supplying at an industrial scale remains limited.

Can the Industry Really Move On?

In practice, a sudden break from the Portland process is unlikely. The installed base of kilns, standards, and construction codes is simply too large. What looks more realistic is a gradual shift toward hybrid systems — lower clinker content, higher use of alternative mineral feedstocks, and selective use of additives where performance or carbon savings justify the cost.

It is a slow and steady transition with great significance for chemical traders, as demand is likely to grow for calcined clays, alkaline chemicals, specialty additives, and locally sourced mineral streams. At the same time, traditional limestone and fuel markets will likely face increasing competition and smaller margins as the use of alternatives grows alongside carbon taxes and regulatory pressure.

Ultimately, cement manufacturers will not abandon Portland chemistry overnight, but the industry’s raw-material mix is already changing. As customers become increasingly nervous over energy prices, carbon costs, and supply security, these factors will become just as important as compressive strength.

For the wider chemical industry and its suppliers, it is an industrial shift which will create a steady flow of opportunities—not just to sell greener materials, but to help redefine what “standard” cement really means.

Photo credit: wirestock, flickr, researchgate, wirestock, & Gencraft