-

Fighting Chemophobia with Common Sense

Continue Reading

Continue ReadingThere is a new movement making waves in suburbia. It is a force for good that is applying common sense to the way we live our lives, and to the way that we raise our children. It is a way of thinking that reduces fear, and instead applies common sense to everyday problems. Interestingly, it is having great success in allaying people’s fear of industrial chemicals.

It is being lead by the wonderfully named Julie Gunlock, and her book, ‘From Cupcakes to Chemicals’, and is based on a healthy examination of the risks in daily life coupled with a common-sense look at the dangers that the chemicals in our lives present.

One of the more amusing and yet relevant stories from the book, includes that tale of how the author was watching a news report on the dangers of drinking water from a garden hose. Where she writes that, “The news story centered on the fact that most garden hoses are made of polyvinyl chloride, better known as PVC. PVC has high levels of lead and other chemicals and, therefore, the claim was that since children and pets sometimes drink from garden hoses, they were getting big doses of toxins when taking the occasional sip.”

Gunlock then continues to question the logic behind the news story, asking, “Most garden hoses are indeed made of polyvinyl chloride, which is toxic if consumed in large quantities. Yet it is impossible — let me repeat that word, impossible — for a human to consume enough water to reach toxic levels of PVC exposure. Why is this impossible? Because the amount of chemical that leaches into the water is so minuscule that a person would have to consume massive amounts of garden hose water in order for it to be a problem. And if a person attempted to drink the amount of water required to reach PVC toxicity, they’d first die of dilutional hyponatremia — death by water overdose.”

Gunlock goes on to explain the real tragedy of this case, and of chemophobia in general, and that is the fear that people are living with. They worry that the ‘bogeyman’ (a.k.a. industrial chemical manufacturers) will get them and their children. Their lives are hampered by this fear, and as a result, their children’s youth is restricted.

Is Fake News to Blame for Chemophobia?

A fair analysis of the garden hose news story would not make for much of a story. ‘Garden hoses safe to drink from; shock!’ does not sell newspapers, or drive traffic to a website. Instead, to fill a paper’s column inches or to act as ‘clickbait’, journalists are content to fly in the face of logic.

Creating half-true stories is something that has an impact on everyday lives, as Gunlock writes, “Alarmist warnings often distract parents from the real dangers and legitimate risks facing kids. Nervous parents who feel overwhelmed by the conflicting reports about what’s safe and what’s not deserve a little honesty and should be spared the constant drum beat of hysteria that comes from environmental, food and public health nannies.”

There has been much written about fake news stories in the media since the Brexit referendum and Trump’s presidential election victory. The reporting is as if this is a new phenomenon, a product of the digital age that is only now altering public opinion. But given the decades of negative news against the chemical industry, and the continued, irrational presence of chemophobia, perhaps fake news stories are not as new as we might think.

Photo credit: https://openparachute.wordpress.com/2016/03/20/the-toxicity-of-chemophobia/chemophobia/

-

Capturing Toxic Chemicals with a Soy Protein based Air Filter

Continue Reading

Continue ReadingResearchers have developed an environmentally-friendly air filter made from simple soy proteins. Better still, the research team claims that the design is more effective at catching particles than regular air filters, and is specifically able to capture gaseous particles such as carbon monoxide and formaldehyde. This makes the discovery not only timely, given the impact that air pollution is having on major cities throughout the world, but also ideal for the growing chemical industry or those who live near industrialized areas.

The online scientific journal, Phys.org, notes how the breakthrough was made by, “… researchers from the University of Science and Technology Beijing, and [a team from] the Washington State University, including Weihong (Katie) Zhong, professor in the School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, and graduate student Hamid Souzandeh,” who, they explain, “used a pure soy protein along with bacterial cellulose for an all-natural, biodegradable, inexpensive air filter.”

While the use of such natural materials may seem obvious from an environmental perspective, the Washington State University website also outlines the economic advantages and logical thinking behind such a decision, stating that, “The soy protein and cellulose are cost effective and already used in numerous applications, such as adhesives, plastic products, tissue regeneration materials and wound dressings. [Furthermore] Soy contains a large number of functional chemical groups – it includes 18 types of amino groups, with each of the chemical groups having the potential to capture passing pollution at the molecular level.”

As Zhong notes, “We can take advantage of those chemical groups to grab the toxics in the air.”

She and her fellow researchers have now published their results in the journal, Composites Science and Technology, reporting that, “…conventional petroleum-based and chemically synthesized polymers [currently used in] commercial air filters are not eco-friendly materials and can cause secondary environmental pollution. To address this serious issue, the development of an environmentally friendly and multi-functional air filtering material is a critical need. In this study, soy protein isolate (SPI) and bacterial cellulose (BC) are employed to study the potential of biomaterials as high efficiency air filtering materials. Soy protein isolate contains many functional groups on its structure and these functional groups were exposed for interactions with pollutants via a denaturation process using acrylic acid treatment. The 3D nano-network of BC contributes to the preliminary physical capturing of PM particles, while the functional groups of SPI further attract the PM particles via electrostatic attraction and dipole interaction between the filter materials and the PM particles.”

The results from the study proved promising, claiming that, “The SPI/BC composite with an appropriately modified SPI possesses extremely high removal efficiencies for particulate pollutants with a broad range of sizes: 99.94% and 99.95% for PM2.5 removal efficiency and PM10, respectively, under extremely hazardous air conditions, while maintaining a very high air penetration rate of 92.63%.”

While naturally pleased with the added effectiveness of the soy-protein air filter, Zhong was keen to underline the advantages the filter had over those currently in use, saying, “Typical air filters, which are usually made of micron-sized fibers of synthetic plastics, physically filter the small particles but aren’t able to chemically capture gaseous molecules. Furthermore, they’re most often made of glass and petroleum products, which leads to secondary pollution.”

She also notes that there is a clear market for her product, saying, “Air pollution is a very serious health issue. If we can improve indoor air quality, it would help a lot of people.”

With this in mind, the team are continuing their work as they believe there are real practical advantages to their design of chemical filter, as the Phys.org explains, “In addition to the soy-based filters, the researchers have also developed gelatin- and cellulose-based air filters. They are also applying the filter material on top of low-cost and disposable paper towels to reinforce and improve its performance. They have filed patents on the technology and are interested in commercialization opportunities.”

Given that regular air filters are not especially efficient, and are generally aimed at removing larger pollutant particles, the fact that an improved device has arrived at a time when public awareness of the dangers of air pollution is higher than ever is significant. Even more important, is the fact that the filter is able to remove, “hazardous gaseous molecules, such as carbon monoxide, formaldehyde, sulfur dioxide and other volatile organic compounds.” Meanwhile its low cost and environmentally-friendly credentials are sure to have customers lining up for fresher air.

Photo credit: Elsevier B.V.

-

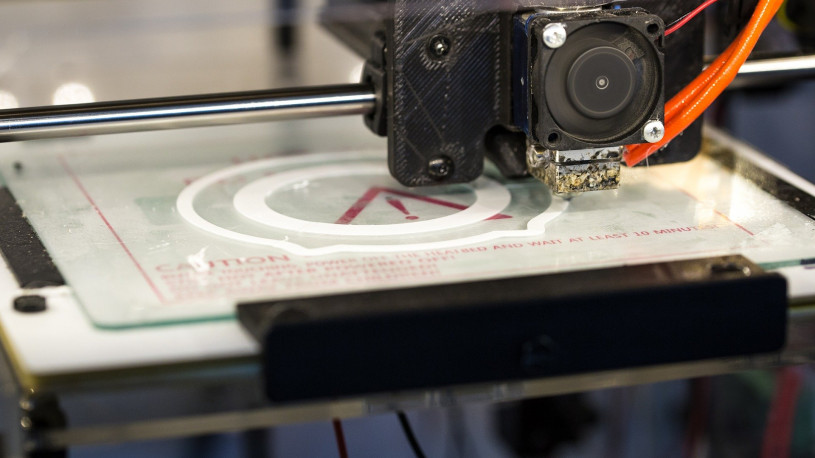

A Process to Chemically and Mechanically Change 3D Printing Polymers, Even After Printing

Continue Reading

Continue ReadingChemists from MiT have developed a process that potentially enables the polymers used in 3D printing to be altered, even after they have been printed.

Up to now, once polymers have been printed, they are considered ‘dead’ and no changes can be made to the polymer chains, but now, the door has been opened for monomers to be added that can amend the chemical and mechanical composition of printed plastics. This enables the researchers to adjust the size of printed objects, add water repellent properties, or even to fuse two printed objects together, simply by shining light on them, opening a world of far more complex 3D printed constructions.

Jeremiah Johnson, the Firmenich Career Development Associate Professor of Chemistry at MIT, explained the concept as, “The idea that you could print a material and subsequently take that material and, using light, morph the material into something else, or grow the material further.”

The story began in 2013, when, as the online journal Phys.org reports, “Johnson and his colleagues [former MIT postdoc Mao Chen and graduate student Yuwei Gu] set out to create adaptable 3-D-printed structures by taking advantage of a technique known as ‘living polymerization’, which yields materials whose growth can be halted and then restarted later on.” The journal continues by describing how the researchers found, “that they could use a type of polymerization stimulated by ultraviolet light to add new features to 3-D-printed materials. After printing an object, the researchers used ultraviolet light to break apart the polymers at certain points, creating very reactive molecules called free radicals. These radicals would then bind to new monomers from a solution surrounding the object, incorporating them into the original material.”

Johnson outlined the clear benefit of this at the time, saying, “The advantage is that you can turn the light on and the chains grow, and you turn the light off and they stop. [So that], in principle, you can repeat that indefinitely and they can continue growing and growing.”

Now the research team has taken their discovery to the next level, in a way that makes 3D printing a much less permanent result. The journal MiT News, notes how this latest breakthrough is an addition to their previous research, stating, “In their next effort, the researchers designed new polymers that are also reactivated by light, but in a slightly different way. Each of the polymers contains chemical groups that act like a folded up accordion. These chemical groups, known as TTCs, can be activated by organic catalysts that are turned on by light. When blue light from an LED shines on the catalyst, it attaches new monomers to the TTCs, making them stretch out. As these monomers are incorporated uniformly throughout the structure, they give the material new properties.”

“That’s the breakthrough in this paper: We really have a truly living method where we can take macroscopic materials and grow them in the way we want to,” said Johnson.

The researchers have published their results in the ACS journal Central Science, declaring that, “we have developed a first-generation living additive manufacturing process called ‘photoredox catalyzed growth‘ (PRCG) that enables the controlled insertion of monomers and cross-linkers into polymer networks to produce complex daughter objects from a single type of parent object. PRCG makes use of a newly developed photoredox catalyzed polymerization that avoids the undesired chain termination processes that are present in traditional free radical and iniferter polymerizations. Our approach enabled the fabrication of daughter gels with complex compositions and mechanical properties that would be difficult or impossible to achieve using traditional free radical polymerization methods.”

These monomers are able to adjust chemical and mechanical properties, such as stiffness or hydrophobicity (affinity for water), as well as swelling or contracting under temperature stimuli.

While the researchers acknowledge that the process still needs a lot of refining, stating that, “For practical applications, PRCG will require extensive development: the polymerization rate should be increased by at least an order of magnitude, the oxygen tolerance should be thoroughly investigated, and the expansion to bulk polymeric materials should be pursued.” Also, their work to date has also largely focused on gels, but they also make clear that their work is ongoing, and that numerous alternative catalysts are already being tested that are not affected by the presence of oxygen.

If these limitations are overcome, then 3D printing as a real-world production process may really begin to take-off. The idea that plastics can be printed and then amended, chemically or mechanically, by applying light is sure to attract the interest of polymer traders and plastics manufacturers worldwide.

Imagine, for example, how products could be improved if the consumer were able to fuse plastics parts together by shining a light at the joint. While other products could also be amended, for example, so that they travel flexible and can then be made rigid, or made hydrophobic, or made softer, or expand, or contract. Are these the 21st century polymers we’ve been waiting for?

Photo credit: Demin Liu and Jeremiah Johnson

Photo credit: American Chemical Society