EU Cobalt Plan Raises Raw Material Supply-Chain Risk

Will new safety limits on cobalt processing further undermine Europe’s chemical industry?

Europe’s cobalt value chain is facing a regulatory shock that could reshape the continent’s ability to produce advanced materials, battery chemicals, and speciality intermediates.

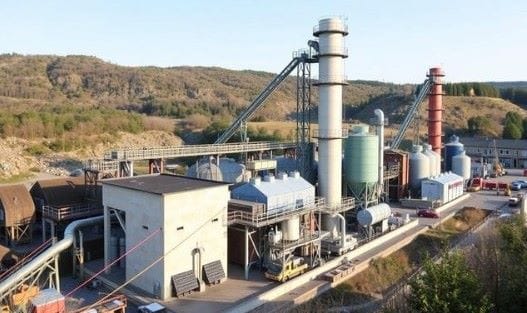

Proposed new EU workplace-exposure limits for cobalt dust—part of the revision to the Carcinogens, Mutagens and Reprotoxic Substances Directive (CMRD)—have triggered warnings from major producers and manufacturers, who argue that the rules risk pushing cobalt refining out of Europe altogether. For a region that has built its industrial strategy around securing critical raw materials, the possibility of losing domestic cobalt capacity is more than an inconvenience: it may be a strategic setback.

The Commission argues that stricter limits on occupational exposure are necessary to reduce long-term risks of cancer and other respiratory illnesses, estimating that the changes could prevent up to 1,700 lung-cancer cases over four decades. While few dispute the importance of protecting worker health, the cobalt industry argues that the proposed limits are far more stringent than those used by global competitors.

Under the proposal, the European Commission intends to introduce strict new occupational exposure limits (OELs) for cobalt and inorganic cobalt compounds. The planned threshold is 0.01 mg/m³ for inhalable dust and 0.0025 mg/m³ for respirable dust, with an interim six-year transitional limit of 0.02 mg/m³ and 0.0042 mg/m³, respectively.

For context, the United States maintains an exposure limit of 0.1 mg/m³, and China uses 0.05 mg/m³. The proposed European level is therefore an order of magnitude tighter. Producers argue that reaching 0.01 mg/m³ is technically possible, but only with costly plant redesigns, new filtration systems, and operational changes that may erase already thin margins. This is especially true because cobalt refining is energy-intensive and highly regulated, with Europe already considered a high-cost region.

Adding further compliance burdens, the industry warns, will push companies to shift existing or planned capacity to jurisdictions where the regulatory environment is less prohibitive. Such a reaction would undermine the EU’s ability to control supply chains for electric vehicles, renewable energy technologies, and a wide range of speciality chemicals.

Related articles: EU-Australia Deal to Reshape Raw Material Supply or A Greener Way to Source Rare Earth Elements: Bio-Mining

Industry leaders have communicated their concerns directly to Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, arguing that cobalt producers are not opposed to tighter exposure limits but believe that the proposed thresholds are disproportionately low compared with international benchmarks.

A recent Financial Times report quotes a letter to von der Leyen signed by twelve leading cobalt producers—including Glencore and Umicore—stating that, “The damage is already being felt, [as] companies are diverting investment away from the EU.” Adding that the proposals would “only result in greater dependence on the US and China for materials that are strategic to defence and vital to the green, circular and digital transitions.”

Where does this leave Europe’s chemical sector?

Cobalt is an essential input for catalyst manufacturing, high-temperature alloys, pigments, and a wide range of battery materials. Even small disruptions to supply can reverberate through the speciality-chemicals market. If the new regulations are imposed, then chemical traders may face increased volatility if domestic refining retrenches, while downstream manufacturers could find themselves more dependent on imports from China or other third countries, despite the EU’s political commitment to “strategic autonomy” in critical materials.

In this context, the cobalt debate exposes a deeper tension: how to balance safety regulation with the practical realities of industrial competitiveness. This is an issue which was hoped to have been resolved with the introduction of the EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), which entered into force in 2024—a way to build resilient supply chains for strategic minerals alongside European sentiment for human rights and environmental welfare. Yet if EU rules make local production economically prohibitive, the bloc may be forced to rely on external raw material suppliers—precisely the outcome the CRMA was designed to avoid.

The current situation also raises questions about the EU’s broader decarbonisation agenda. Electric-vehicle supply chains are already under scrutiny for their dependence on imported materials. If cobalt refining also leaves Europe, the region’s battery-materials industry may struggle to meet demand or may need to rely more heavily on imported precursor chemicals. This could increase carbon footprints, lighten the leverage Europe holds over supply-chain governance, and raise costs for domestic manufacturers.

Chemical-industry traders and manufacturers should therefore treat the cobalt debate as a strategic signal. The final outcome of the OEL negotiations will influence investment decisions, supply-chain architecture, and raw material pricing for years to come.

Although the regulatory process is still ongoing, the stakes are clear. Europe must find a coherent way to protect workers without hollowing out the domestic chemical industry that underpins its green-technology ambitions. The cobalt debate is more than a regulatory technicality; it is a test case for whether Europe can pursue public health, industrial resilience, and global competitiveness simultaneously.

Photo credit: msvr on Pexels, gencraft, & getpxhere